Jeddah’s awe-inspiring Al Makkiyah mansion

Former US President Jimmy Carter and US consulate staff listen as Dr. Sami Angawi speaks about Islamic art, science and history at Al Makkiyah. (Click photos to enlarge.)

Leaders come to Al Makkiyah

One of the most interesting private residences in Saudi Arabia is the home of well-known architect and historian Dr. Sami Angawi. Al Makkiyah mansion attracts leaders and visitors from around the world.

Angawi is an expert in Islamic architecture and is also outspoken about his faith, Islam. The house serves as a meeting place for individuals and groups seeking to communicate Middle Eastern culture to peoples and groups on other continents. He believes, however, that extremists are attempting hijack Islam. He and other Muslim leaders hope to maintain Islam’s core roots—balanced and moderate and more tolerant of people’s differences.

Angawi is known for his activism–especially his strong views about historic preservation in the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. Many significant sites of Islam have been destroyed under direct orders from radical religious leaders in an effort, they claim, to prevent idolatry or because of what they consider to be,the veneration of gravesites or relics. (See my story “Grandmother Eve’s grave.”)

Public lectures and concerts

The Angawi house is a cultural haven in Jeddah where his family and friends regularly host lectures, concerts and timely discussions, often on a weekly basis.

The design of this residence combines modern construction techniques with traditional crafts such as Turkish mosaic and Moroccan zillij. Red Sea coral reef stone, desert sandstone, marbles and granite are utilized throughout the exterior and interior.

Old-style natural ventilation techniques minimize the need for air-conditioning even at the peak of hot Arabian summers. A computerized drip-watering system feeds thousands of hanging plants that are an integral feature of both the central internal courtyard and the exterior ground and roof gardens.

The Islamic principle of sitr (ensuring privacy for neighbors as well as inhabitants of the house) is accomplished by using traditional rawasheen bay windows and intricate hand-carved Hijazi woodwork over the openings.

Al Makkiyah will serve as the main campus of the Al Makkiyah/Al Mediniyah Institute for cross cultural studies.

Bridging nations and faiths

For decades Saudi Arabia has been generally considered a somewhat closed society, eager to protect its own traditions from external cultural influences.

While preservation of traditions is of great concern to Dr. Sami Angawi, his desire is balanced with a passion for building bridges between nations, cultures and faiths.

His architectural designs assert the importance of his HIjazi heritage with the common cultural heritage shared by both western and Islamic societies; believing that a “clash of civilizations” need not lead to misunderstanding, but rather friendship, trust and peace.

This concept of balance, known in Arabic as mizan, is the essence of Islamic tradition and of many of the world’s religious beliefs. The aspiration of Angawi to reflect this historic principle in his life and work is important. It has made him a leader in building bridges between the Middle East and the rest of the world. “More balance can be achieved through respect for the past,” Angawi says. “In our Al Makkiyah mansion, modernity and tradition, privacy and openness, stability and dynamism are equally represented to generate harmony.”

Hijazi culture influences the modern world

Angawi is the founder of the renowned Hajj Research Center in Mecca and also the Amar Center for Architectural Heritage. He has dedicated his life to preserving the history and architecture of Islam’s holy cities of Mecca and Medina; encouraging dialogue about Islam and cross-cultural collaboration and understanding between institutions and universities worldwide.

Angawi’s Hijaz ancestry can be traced back to the Mecca region along the central Red Sea coast. It is his lineage, dating back to the time of the Prophet Mohammed, that has formed his religious thought. “The Hijaz,” he says, “is the site of Islam’s holy places and the melting pot of the Muslim world. Millions of pilgrims from all over the world have traveled annually for centuries to the region, enriching it with their traditions and ideas.”

Respect and compassion

Angawi believes that respect, solidarity and compassion are human values and inspiring principles for every culture and all faiths. “Being aware of these intrinsic similarities and stressing them is the only antidote to fear, bigotry and ignorance.”

In a 2011 interview with Arab News, Angawi said, “Al Makkiah represents a seed. I wish that one day we could have thousands Al Makkiyahs and establish a ‘United Nations of people,’ regardless of their race, color or beliefs.”

When Arab News challenged his concept as being Utopian, Angawi said he finds inspiration in water. “It is a powerful element, stronger than rocks, steel and diamonds. If it doesn’t reach the sea, water changes its status and comes back in other forms to achieve the goal.”

Al Makkiyah/Al Mediniyah Institute

Dr. Sami Angawi is now gathering an international board of intellectuals, activists and businessmen to create his legacy–an international institute offering degrees in Islamic history and science, the Al Makkiyah / Al Mediniyah Institute will provide courses in Islamic history, architecture and science.

The institute at Al Makkiyah will house Angawi’s more than 100 thousand photographs, drawings and writings about Islam and the two holy cities Mecca and Medina. The school will be a collaborative educational experience, providing American, Canadian and European students the opportunity to research Islam on location in the Hijaz–right where the faith has advanced over the past 1400 years.

Here’s a short video describing the Al Makkiyah mansion:

Sources: Arab News, wikipedia.com, Saudi Airlines, CNN, History of Architecture, BBC, Harun Yahya TV

Ascending the minaret–a childhood dream

Dream come true

Today my friend Aidarous Al Mashhour drove me to the Khalil Mosque here in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. After we prayed together at the mosque, Aidarous told the imam about my childhood dream—to climb to the top of a minaret.

The imam directed us to the caretaker of the mosque who was more than happy to unlock the door to the inner stairway of the minaret. After some ten minutes of climbing through very narrow openings I arrived at a balcony which encircles the upper section of the minaret. I was so happy to be able to look out over the city of Jeddah and to consider the hundreds of years of Islamic history that minaret represented..

The history of this marvelous structure

The minaret is one of the most distinctive features of a mosque. It’s history is interesting, not just to Muslims, but also in the annals of architecture.

Remarkably, there are very few references to the minaret in Arabic literature.

The name itself is somewhat strange, and in no way represents the purpose for which these towers are built. The word in Arabic means “an object that gives light” ((Arabic nur, meaning “light”; hence mi-nur-rat or minaret). So, from the name itself one could wrongly conclude the minaret to be a type of “light house” or tower with a light on top.

Some suggest that the minaret gets its name from the light that the muadhin (“caller to prayer”) would hold as he recited the adhan (call to prayer). Others indicate that in some of the oldest mosques, such as the Great Mosque of Damascus, minarets doubled as illuminated watchtowers.

The earliest Islamic mosques had no minarets. The mosques built in the days of the Prophet Mohammed in Mecca and Medina were very simple. There was nothing like a tower associated with these early houses of prayer and worship.

The call to prayer

Sam’s friend Muadhin Shafik Zubir calls the faithful to prayer five times a day at Taqwa Mosque near the Red Sea promenade in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

The use of the adhan goes back to the lifetime of the Prophet Mohammed. The adhan is, for sure, one of the most characteristic, powerfully evocative symbols of Islam. This Arabic call to prayer, dramatically intoned by a muadhin from high atop a lofty minaret—once heard—it can never be forgotten!

The use of the adhan goes back to the lifetime of the Prophet Mohammed, and is mentioned only once in the Qur’an, in connection with the Friday assembly:

“O you who have believed, when [the adhan] is called for the prayer on the day of Jumu’ah [Friday], leave your business and proceed to the remembrance of God. That is better for you, if you only knew” (Sura 62:9).

Muslim tradition explains how the adhan came to be used to announce the times of the five daily prayers.

After the emigration of Mohammed and his followers from Mecca to Medina (known as the Hijra) a believer named Abd Allah ibn Zaid had a vision in which he tried to buy a wooden clapper to summon people to prayer, as was the tradition of Christians living in Medina at that time. But the man who had the clapper advised him to call out to the people instead and to cry:

God is the greatest! God is the greatest!

I testify that there is no god but God.

I testify that Muhammad is the Prophet of God.

Come to prayer! Come to prayer!

Come to salvation! Come to salvation!

God is the greatest! God is the greatest!

There is no god but God!

Bilal, Islam’s first “caller to prayer”

According to Ibn Ishaq, the eighth-century biographer of Prophet Mohammed, Ibn Zaid went to the Prophet with his story and Mohammed, having had a similar dream, agreed. He told Ibn Zaid to ask an Ethiopian believer named Bilal, who had a marvelous voice, to call the Muslims to prayer.

Early traditions indicate that Bilal made his call to prayer from the rooftop of the Prophet’s house, which doubled as a residence and a place for prayer and worship.

Indeed, no towers were used or mentioned. The ancient poet al Farazdak spoke of the adhan as being prounounced “on the wall of every city.” In the later hadiths it was said “the muadhin, if he is on the road, may make the call to prayer while riding; he need not halt.”

(Note: Below, I have put a short, stirring video of the call to prayer being made from the minarets of Jeddah. Listen to it.)

First mentions of minarets

The first time a minaret is referenced in connection with the mosque was in Medina–some 80 years after the Prophet Mohammed’s passing.

The massive minaret of the Great Mosque of Kairouan in Tunisia is the oldest standing minaret. Its construction began during the early 8th century and was completed in 836 CE. Its imposing square-plan tower consists of three sections of decreasing size reaching 31.5 meters (103 feet). Considered as the prototype for minarets of the western Islamic world, it served as a model for many minarets to come.

The tallest minaret, at 210 metres (689 ft), is located adjacent the Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca, Morocco. The tallest brick minaret is the Qutub Minar in Delhi, India.

Perhaps you heard recently about the 12th-century Great Umayyad Mosque in Aleppo, Syria. It was a UN World Heritage Site. Sadly, its ancient minaret was completely obliterated a few months ago during a battle of the ongoing Syrian Civil War.

The minaret’s design

Minarets basically consist of three parts: a base, shaft, and the tower gallery. For the base, the ground is excavated until a hard foundation is reached. Gravel and other supporting materials may be used as a foundation.

Minarets may generally tapered upward, square, cylindrical, or polygonal (faceted). Stairs circle the shaft in a counter-clockwise fashion, providing the necessary structural support to the decidedly elongated shaft.

The gallery is a balcony which encircles the upper sections from which the muadhin may give the call to prayer. It is usually covered by a roof-like canopy and adorned with ornamentation, such as decorative brick and tile work, cornices, arches and inscriptions, with the transition from the shaft to the gallery typically sporting muqarnas (collections of small corbels that form a transition from one plane to another). Formerly plain in style, a minaret’s place in time can be determined by its level of embellishment.

The symbolic moon

The crescent moon, sometimes combined with a star, often tops the minaret. This symbol was often used by the late Turkish Ottoman Empire; however, its not the official symbol of Islam.

In many nations; however, it remains a generally accepted symbol of Islam in much the same way the Star of David represents Judaism or as the cross is representative of Christianity.

The crescent moon points to God’s awesome creation. We read in the Qur’an, “Surely your Lord is none other than God, Who created the heavens and the earth in six days, and then ascended His Throne; Who causes the night to cover the day and then the day swiftly pursues the night; Who created the sun and the moon and the stars making them all subservient to His command. Lo! His is the creation and His is the command. Blessed is God, the Lord of the universe” (Qur’an 7:54-58). A similar sentiment is echoed by the prophet King David in the Psalms, “When I consider your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, which you have set in place, what is mankind that you are mindful of them, human beings that you care for them?” (Psalm 8:3-5).

The crescent moon is not, as some Islamophobic individuals continue to wrongly assert, a “secret Muslim moon god”! The Qur’an forbids the worship of idols of any kind. “And from among His signs are the night and the day, and the sun and the moon. Do not bow down (prostrate) to the sun nor to the moon, but only bow down (prostrate) to God Who created them, if you (really) worship Him” (Qur’an 41:37).

Watch this short BBC report on Jeddah’s mosques and the call to prayer:

Sources: The Oxford History, wikipedia.com , Saudi Aramco World, BBC, CNN, Architectural History

The Egyptian pyramids and the mummy’s curse!

My visit to the pyramids of Giza

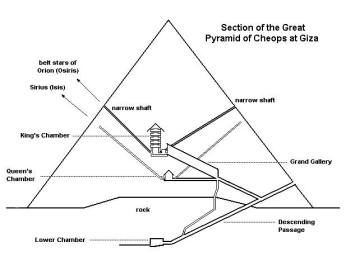

I recently fulfilled a lifetime dream of visiting the famous Pyramids of Giza, just to the south of Cairo, Egypt. These celebrated pyramids are among the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the oldest built more than 4500 years ago! Modern scholars and archaeologists have long been curious about these ancient tombs of the pharaohs. Out of the three pyramids, the most famous is the Great Pyramid of Khufu (Cheops), which was built by Pharaoh Khufu around 2560 BC.

Sam standing among the collosal, ancient limstone blocks that were used to build the Great Pyramid of Pharaoh Khufu. (Click on photos to enlarge.)

The Great Pyramid stands 137 meters (449 feet) high. Each side is oriented with one of the cardinal directions of the compass (north, south, east, and west). The Great Pyramid of Khufu is made up of two million blocks of limestone. Granite lines the entrances, the shafts and the chambers. The thousands of smooth white casing stones that beautified the sides of this pyramid, have long since been unfortunately removed, being used in other building projects.

I was pleasantly surprised when my Egyptian friends actually got permission for me to climb through the inner shafts of the Great Pyramid. This pyramid is equal in height to a modern 50-story skyscraper! For the better part of an hour, I was led upward through the narrow connecting shafts some 200 meters (656 feet) to the upper chamber of Khufu. Due to low ceilings in most of the shafts, one is forced to lean over while walking, literally crawling, in places, on hands and knees. It was a difficult climb, and I was drenched in sweat when I finally stood in the burial chamber of Pharaoh Khufu.

The Pyramid of Khafre (Chephren) is situated to the southwest of the Pyramid of Khufu. Although it appears to be taller than the Great Pyramid, as it stands on higher ground, this pyramid is actually smaller than that of Khufu. This pyramid was built by Khufu’s son Khafre.

The third pyramid, the Pyramid of Menkaure (Mycerinus), which stands some 67m (220ft) high, was started by Khafre’s son Menkaure.

In front of the Great Pyramid stands the Sphinx, a statue of a creature with the body of a lion and the head of a man. The Sphinx, which stands 20 meters (66 feet) high, and measuring about 73.5 meters (241 feet) long, was carved over 4500 years ago out of sandstone.

Archaeologists and historians marvel

Can you imagine one of our modern skyscrapers weathering 4500 years of harsh climatic conditions? Just how were these pyramids built? How have they stood the test of time?

Today’s scientists, historians and civil engineers stand in awe of the pyramids. They are continually developing theories as to just how the ancient Egyptian peoples could have carved and moved these millions of huge stones hundreds of miles from the far south to their Giza location and then haven assembled them into the pyramids.

When I was in graduate school, I remember reading the 1970 best-selling book by Erich von Däniken‘s titled Chariots of the Gods. The book theorized extraterrestrials interacting with early human life, passing on high-tech scientific information to undeveloped human civilizations in various parts of the world—one being the ancient kingdoms of the Egyptian pharaohs. (This theory was subsequently debunked by University of South Carolina professor Dr. Clifford Wilson in his 1972 sequel entitled Crash Go the Chariots.)

One of the best construction explanations I’ve found was published in the March 2008 issue of Science Daily.

The legendary curse of the pharaohs

Just two days after climbing through the Great Pyramid’s inner, narrow shafts leading to Khufu’s burial chamber, I ended up in a Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, hospital with a high temperature, swollen glands diagnosed with some mysterious, unknown virus. I was mainlined with some pretty powerful antibiotics for five days and then released to continue my recuperation at home. I have now fully recovered, but I couldn’t help but wonder about all the extraordinary rumors of pyramid curses that have circulated for centuries.

Movies and sensational Hollywood science fiction movies abound, encouraging the rumors—the classic being the 1944 horror film The Mummy’s Curse.

The idea of a mummy coming back to life from the dead, an essential part of many mummy curse legends, was developed in The Mummy! Or a Tale of the Twenty-Second Century, an early work combining science fiction and horror, written by Jane C. Loudon and published in 1827.

Louisa May Alcott was thought by Dominic Montserrat to have been the first to use a fully developed plot about the “mummy curse.”

Two other stories subsequently discovered by S. J. Wolfe, Robert Singerman and Jasmine Day–The Mummy’s Soul (Anonymous 1862) and After Three Thousand Years by Jane G. Austin in 1868–have similar plots. In both, a female mummy takes supernatural revenge upon her male counterpart.

Tutankhamun’s “curse”

The belief in a curse was brought to many people’s attention due to the mysterious deaths of several members of archaeologist Howard Carter‘s team while they were excavating the tomb of Tutankhamun (more commonly known as King Tut). The tomb was located far to the south in the Valley of the Kings and was opened by Carter and George Herbert, the Fifth Earl of Carnarvon (Lord Carnarvon) in 1922.

The famous Egyptologist James Henry Breasted, working with Carter soon after the first opening of the tomb, reported how Carter had sent a messenger on an errand to his house. When the man came near to Carter’s home he thought he heard a “faint, almost human cry.” On reaching the entrance he saw a cobra in a bird cage. (The cobra was the symbol of Egyptian monarchy.) Carter’s canary had died in the cobra’s mouth, and this fueled local rumors of a curse. An account of the incident was reported by the New York Times on 22 December 1922. The first of the “mysterious” deaths was that of Lord Carnarvon. Carnarvon had been bitten by a mosquito, and later cut the bite accidentally while shaving. It became infected and blood poisoning resulted.

Two weeks before Carnarvon died, Marie Corelli wrote an imaginative letter that was published in the New York World magazine, in which she quoted an obscure book that confidently asserted that “dire punishment” would follow any intrusion into a sealed tomb. A media frenzy followed, with reports that a curse had been found in the King’s tomb, though this was untrue.

The curse rumors were further fanned by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes. In a film he suggested that Lord Carnarvon’s death had been caused by “elementals” created by Tutankhamun’s priests to guard the royal tomb, and this further fueled public curse frenzy. .

A newspaper report printed following Carnarvon’s death is also believed to have been responsible for the wording of the curse most frequently associated with Tutankhamun – “Death shall come on swift wings to him who disturbs the peace of the King.”

There is, though, a possible reasonable explanation for illness and even death resulting from noxious gases that are released when ancient tombs are opened. When Archaeologist Sami Gabra was working in tombs in the ibis-necropolis of Tuna el-Gebel, both he and his workers were seized by violent

Lord Carnarvon died six weeks after the opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb. His death resulted in many curse stories in the media.

headaches and shortness of breath. At first the workers feared of the ibis-headed god, Thoth. In reality, it was discovered that the cause was toxic vapors. When the tomb was fumigated, the crew returned to work..

Russians scale the Great Pyramid

A few months ago, Russian photographer Vadim Makhorov caused quite a stir when he published a set of stunning images captured from atop Egypt’s Great Pyramid. The photos, posted to Makhorov’s LiveJournal page, provide a rare view of one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, though they’ve fueled a fair bit of controversy, as well.

Once the pyramid complex had closed to tourists, Makhorov and his two friends, Vitaliy Raskalov and Marat Dupri, staked out for nearly five hours, hiding themselves from Egypt’s armed guards. (Now if only I had been there to scale the pyramid with these guys!)

When they were certain the coast was clear, they embarked on the 481-foot climb to the top of the pyramids, where they captured incredible panoramic shots of the Giza Necropolis,. They were able to keep totally out of sight of the guards below.

According to Raskalov, the trio would have faced between one and three years in jail, had they been caught. Said Makhorov, “We didn’t want to insult anyone. We were just following our dream.”

Below are some of the photos Makhorov and his friends took.

Here’s an incredible video about the Great Pyramid of Giza:

Sources: Science Daily, The New York Times, New York World, Archaeology, The Pyramids of Egypt, BBC, The Verge, The Discovery Channel, National Geographic Magazine, galactic-server.net, en.wikipedia.org

-

Archives

- November 2018 (1)

- June 2018 (1)

- December 2016 (1)

- November 2016 (1)

- June 2016 (1)

- May 2016 (1)

- July 2015 (1)

- March 2015 (2)

- February 2015 (1)

- October 2014 (3)

- September 2014 (2)

- August 2014 (1)

-

Categories

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS